Ten Ideas

Below are the ten most "important" ideas I tried to get across in Beyond Walden.

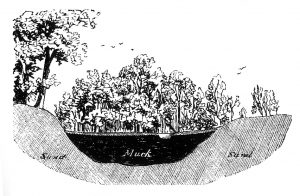

- Fossil Icebergs: Kettles are a special “species” of glacial lake. Borrowing a phrase from nature writer Robert Finch, they are "fossil icebergs," depressions formed when a block of ice became stranded and partially buried with sand and gravel before melting. The special properties of these lakes derive from this origin.

- Transcendentalism: Walden Pond, Massachusetts is the most famous kettle in the world. The chemical purity, surface stillness, hydrological self-reliance, and seasonal moodiness of its water (all characteristic of kettles) contributed importantly to the development of transcendentalist thinking, particularly with respect to light and air. Quoting Thoreau: “Heaven is under our feet a well as over our heads.”

- American History: The band of kettle lakes from Nantucket Island, Massachusetts to beyond Great Falls, Montana, played a supporting role in American history, one masked by the unpretentious and inauspicious character of these lakes. Beginning with the first kettle pond experience by Captain Myles Standish on Cape Cod, they were sources of potable water, beaver pelts, marsh hay, fish, waterfowl, crockery clay, bog iron, wild rice, cranberries, refrigeration ice, herbal remedies and sites of recreation.

- Mississippi River: In a story of international significance, the chaotic nature of the densely kettled ice-stagnation terrain of northern Minnesota helped delay the discovery of the source of the Mississippi River until 1832, more than a quarter century after the Lewis and Clark expedition. Three government-sponsored expeditions with military escorts failed before an Ojibwe guide named Ozawindib brought geologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft to its source. Link to http://kettle.uconn.edu/cultural_geology.html for a historic painting of that event by Seth Eastman.

- Science History: Kettles played a critical background role in the emergence of American science because many are small, self-contained bodies of water surrounded by uniform materials and with deep quiet centers. Their bio-geo-chemical isolation made them ideal natural laboratories for ecology and groundwater hydrology. Their fossil records, which range from butchered mastodons to microscopic pollen, constitute the most important archive for the prehistory and paleoclimatology of the northeastern United States.

- Vulnerable Lakes: Thoreau called Walden a “deep green well.” Given their dependence on groundwater springs draining through silica-rich sand, kettles are highly sensitive to water pollution and especially vulnerable to climate change.

- Family Lake Culture: Inland from the shores of the Great Lakes, practically every lake in the northern heartland states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota is a kettle. There, the recreational development of small lakes in the deep woods near the edge of the prairie led to the emergence of a distinctive regional subculture dominated by winter dreams of summer pastoral retreats.

- Blue Galaxy: Practically every lake south of the hard-rocks of the Canadian Shield, the Adirondacks, and the new England mountains, but north of the outermost glacial limit, is a kettle lake. Collectively, they form a galaxy of approximately 100,000 blue dots on the American landscape. Ranging from the parched prairies of the western high plains and the foggy, boggy moorlands of eastern Nantucket, this galaxy is widest near the center between Michigan’s upper peninsula and central Indiana.

- Freshwater Resource: Climate change, overdevelopment, and a diminished interest in lakes on the part of children are threatening the future of kettle lakes. Learning more about them is a step toward preserving this special, though largely overlooked, freshwater resource.

- Special Ecosystem: Being isolated on the landscape, sunk below the level of the terrain, and surrounded by excessively drained soils, kettles are more nutrient poor than comparably sized lakes.

Etching: 19th century sketch of the geology of a cranberry bog on Cape Cod Massachusetts. From Joseph D. Thomas, ed., Cranberry harvest: A History of Cranberry Growing in the Massachusetts (New Bedford: Spinner Publications, 1990).