Chapter 1 – Rock Reality

Thoreau’s metaphorical path toward simplicity in Walden was downward to what he called the “living rock.” He discovered that the location and form of Walden Pond was controlled by the bedrock at depth, a unit known to modern geologists as the Andover Granite, created deep within the root of an ancient mountain system during the Paleozoic Era, roughly 300 million years ago. Though geology was wildly popular during Thoreau’s era, religious preconceptions about the depth of time, biblical floods, subterranean fires, and the stability of the landscape created great confusion. As part of his geological investigations, Thoreau built a rock and mineral collection, or “cabinet.”

Ancient proterozoic “red” granite of the Avalon Terrane at Bloody Bluff west of Lexington, MA, where British Soldiers experienced heavy casualties during their retreat back to Boston. This durable rock, emplaced along a major fault named after the bluff, is responsible for the drainage divide between the Charles River and the Concord River. Without that divide, there would have been no large glacial lakes, and without them, no meltwater deltas, and without them, no Walden Pond.

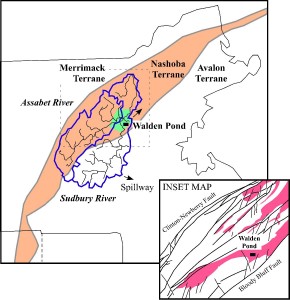

Location of Walden Pond with respect to the town of Concord (green), the watershed of the Concord River (blue outine), the exotic geological terrain known as Nashoba (orange), and the Andover granite (pink), which was intruded up from below along thrust faults. Most of the features of Thoreau Country are aligned by this bedrock structure.

Mineral specimen case built by Thoreau from scrap mahogony, and given to the Reverend Charles Osgood of Cohasset, MA. He was the husband of Ellen Sewall, the young woman Thoreau fell in love with and proposed to before being coldly rejected. Though the specimens shown are those of Osgood, Thoreau had his own little-known collection of specimens as well, which survives intact in storage at the Fruitlands museum.