Chapter 2 – Landscape of Loss

The essential story of Thoreau’s Concord landscape is one of loss. Nearly 300 million years worth of long-term weathering, erosion, and washing away. Called denudation, this loss of weight from the surface raised the former mountain root, whose tectonic grain gave rise to Concord’s corrugated pattern of ridges and valleys and a trellis drainage network. One of these bedrock valleys that was nearly filled with glacial gravel, holds Walden Pond at its associated "Chain of Ponds." Thoreau’s expertise in watershed science and his vocation as a land-surveyor helped him understand of how his landscape came to be.

Concord River, looking north from the dock at the Old Manse to the Old North Bridge, where the "shot heard round the world" was fired on April 19, 1775. Without reading Thoreau’s Journal, the extent to which Thoreau became a self-taught river scientist. He understood not only how they worked as geological agents, but also how they shaped the entire landscape at a regional scale.

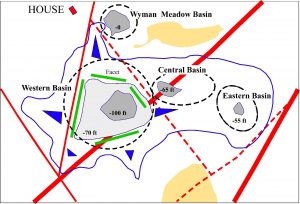

Bedrock faulting at Walden Pond (red lines) created a triangle of weak rock into which its deep western basin was eroded. That bedrock triangle shaped Thoreau’s Cove, fixed the location of his house, and constrained his daily vision to the western basin.

At a larger scale, the Concord landscape is dominated by a series of ridges (resistant rock) and valleys (weak rock) that are aligned northeast-southwest. Four of them are shown in this view looking east from Mount Wachusett. Collectively, they form a trellis pattern to the watershed.

Selvage of roots on the east bank of the Concord River in the Great Meadows. Note the sweeping curve, a feature Thoreau combined with others to create a very sophisiticated conceptual model of 3-dimensional meandering known as helicoidal flow. He was a far better river geologist than Edward Hitchcock, the official "Geologist of the State."